KEYTAKEAWAYS

- The Malu project masks equity financing as RWA using NFT collectibles, separating real yield from users through a tightly controlled SPV model.

- True RWA requires global liquidity, yield-sharing, and decentralized governance—none of which exist in the Malu Grape framework.

- China’s agricultural RWA evolution hinges on off-shore issuance, IoT-backed data integrity, and restoring farmer sovereignty through on-chain cooperatives and DAO governance.

CONTENT

Malu Grape’s RWA experiment reveals China’s asset tokenization dilemma—wrapped in NFT compliance, driven by SPV equity, and stuck between local policy limits and global Web3 ideals.

Read more:

Malu Grape’s “Pseudo-RWA” Breakthrough Part 1

Malu Grape’s “Pseudo-RWA” Breakthrough Part 2

Root Issues: Three Signs of “Pseudo-RWA” Under Local Constraints

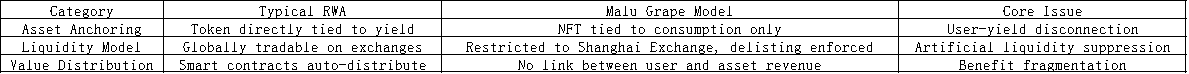

A close analysis of the Malu Grape project reveals that it is not a true Real World Asset (RWA) initiative, contrary to public claims. Here’s why:

Typical RWA tokens represent actual income rights, freely tradable on global markets, with dividends managed through smart contracts. By definition, RWA involves tokenizing real-world physical or financial assets on-chain, enabling decentralized circulation, trading, and management.

In contrast, the Malu project issued 2,024 NFTs strictly defined as digital collectibles, bound only to consumption rights. These NFTs represent grape redemption rights, not potential yield, and come with severe liquidity restrictions, functioning more like agricultural presale vouchers.

In terms of revenue, NFT holders only receive grape delivery cards (worth ¥200–300) and game points, with no share in the data-generated profits. Those profits are reserved entirely for SPV shareholders. While the project claims “token-based revenue sharing,” in reality, the SPV structure isolates income rights from NFT holders.

Governance also remains fully centralized. Decisions such as new varietal adoption or technology upgrades are controlled by the SPV, local government (Malu Town Economic Development Center), and technical providers (e.g., AntChain). Public voting is not available. “On-chain governance” is simply an internal tool of centralized control, deviating from DAO principles.

Ultimately, the Malu Grape project is a government-endorsed financing operation disguised under the RWA concept—a blockchain wrapper covering traditional equity mechanics. Technology here is used to enhance credibility, not decentralize finance—a uniquely Chinese interpretation of RWA.

Breakthrough Pathways: From Regulatory Retreat to Ideal Reconstruction

The duality of the Malu Grape model—technological compromise for survival under regulation—reflects a deeper dilemma in China’s approach to agricultural asset digitization.

Copying its SPV-isolated structure and NFT “de-financialized” path risks locking the sector into a cycle of policy privilege and disempowered producers. True RWA requires confronting three systemic constraints: regulatory restrictions, technical costs, and asymmetrical rights distribution.

Promotion Constraints and Structural Obstacles

- Policy Dependency: The project heavily relies on the Shanghai Pujiang Chain (state-owned blockchain) and government coordination. Most rural areas in China lack such infrastructure. Outside of pilot zones, projects can only issue consumer-oriented NFTs, not income-bearing tokens.

- Technical Cost Barriers: Deploying over 300 IoT sensors across 600 mu means equipment costs exceeding ¥20,000 per mu—unaffordable for smallholders. Low-margin crops (e.g., cabbage) with <5% price premiums cannot recover such investment. Shared county-level IoT platforms may help, but cross-ownership raises legal challenges.

- Standardization Limitations: While grapes offer traceable, standardized data through QR codes and cultivation controls, tea and aquaculture lack clear, objective data protocols. For example, tea quality varies with microclimates and hand-picking skill, making data valuation difficult to standardize or verify on-chain.

The Real Barrier: A Non-Replicable Special Case

Malu is essentially a high-policy, high-premium anomaly. Its tech success only applies to luxury categories like Wuchang rice or Yangcheng Lake crabs. Generalizing the model demands breakthroughs in cost control and data ownership restructuring.

The EU mandates that original data providers (farmers) receive 40% of digital profits. In contrast, the 27 co-ops in the Malu project were only data contributors—not SPV shareholders—and received no profit sharing.

Prerequisites for a True RWA Model

Regulatory Compliance Offshore

Avoid mainland policy redlines by issuing yield tokens in jurisdictions like Hong Kong or Singapore. Underlying assets must have stable cash flows (e.g., charging stations with over ¥30M annual revenue), regulatory approval (via securities licenses), and audited asset disclosures.

Malu’s yield, subject to weather volatility, was reframed as “data value potential,” weakening its credibility as a stable asset anchor.

Technological Penetration

Use oracles (e.g., Chainlink) to sync real-world asset status with token value, ensuring transparency and auditability. Malu stored environmental data on Pujiang Chain but did not upload yield data or automate income distribution.

A genuine RWA would use ERC-3643 smart contracts with built-in dividend modules to distribute returns automatically to token holders.

Dual-Layer Liquidity Architecture

The primary market would sell to qualified investors via licensed exchanges (e.g., HashKey in Hong Kong). The secondary market would operate on decentralized platforms like Uniswap with market maker support for liquidity.

By comparison, Malu NFTs only trade on the Shanghai Data Exchange, with under 10 daily trades and forced delisting in 2025—deliberately suppressing liquidity.

Critical Leap: Domestic Assets + Offshore Financing

The path forward lies in splitting onshore and offshore responsibilities. For example, use the Hainan QFLP scheme as a springboard: data proofs stay within China’s regulatory perimeter, while the SPV issues yield tokens abroad. This structure maintains compliance while gaining capital mobility.

RWA 4.0 in Agriculture: A Staged Roadmap

Short-Term: Hybrid Sandbox Experiments

In pilot zones like Hainan or Hengqin, deploy “consumer NFT + micro-yield” hybrids. For instance, allow 1.5% of durian harvest revenue to be distributed to NFT holders via smart contracts, staying within rebate policy limits.

Launch agricultural data banks for farmers to pledge planting records as collateral—similar to the ¥1.5M bank credit achieved by the Malu model.

Mid-Term: Data Ownership Legislation

Propose laws such as the Agricultural Data Asset Registration Regulation, assigning revenue rights as follows: 40% to farmers (data producers), 30% to co-ops (data integrators), 30% to platforms/governments (infra and compliance costs).

Anchor rights proportions through on-chain records to solve Malu’s governance exclusion problem for smallholders.

Long-Term: DAO-Led Producer Sovereignty

Create cooperative DAOs: farmers receive governance tokens based on land data contribution, consumers vote on varietals.

When IoT sensors detect that a grape variant is 15% more drought-resistant, DAO votes can trigger automated planting expansion, yield forecasts, and income distribution.

This model turns smart contracts into digital-era plows, rebuilding producer identity within the rural digital economy.

A Chinese RWA Paradigm: Global Tech, Local Restructuring

Agricultural RWA’s ultimate value lies in global technology applied to local production logic.

Short term: consumer NFTs are the safest entry.

Long term: DAO-based cooperatives must empower farmers to set data prices and reclaim digital dividends.

Conclusion

The Malu Grape project is a revolution with shackles. When the ideal of decentralization met the fortress of Chinese compliance, it chose to bow before pushing through: using NFTs as a regulatory shield to enable IoT and traceability adoption.

With just ¥200,000 in NFT sales, it leveraged ¥10 million in equity funding to upgrade the entire agricultural stack.

Its dialectical significance is key:

It proves that consumer NFTs are the safest entry in a heavily regulated environment.

It shows that IoT + blockchain enables “asset unbundling,” but liquidity remains the choke point.

And most importantly, it signals that true RWA ends in producer sovereignty—when farmers hold pricing power, innovation becomes revitalization.

Malu’s compromise and progress is not a full-grown tree—but a bent seed, quietly pointing toward the light.