KEYTAKEAWAYS

- The Malu Grape project uses NFTs as a legal wrapper, hiding its core as a traditional equity financing under tight regulatory oversight.

- Public NFT holders receive only grape vouchers, while true yield rights belong to institutional SPV shareholders, revealing a severe value separation.

- Claimed “on-chain governance” is fully centralized, contradicting DAO principles and highlighting a top-down, compliance-first model of China’s RWA localization.

CONTENT

The Malu Grape project in Shanghai sparked debate as China’s first agricultural RWA tokenization attempt—but beneath the NFT hype lies a story of compromised decentralization and constrained innovation.

Read more:

Malu Grape’s “Pseudo-RWA” Breakthrough Part 1

Project Participants and Their Roles

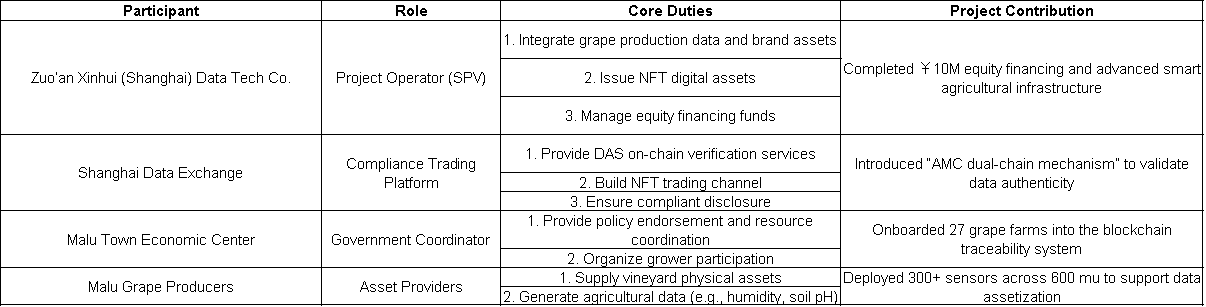

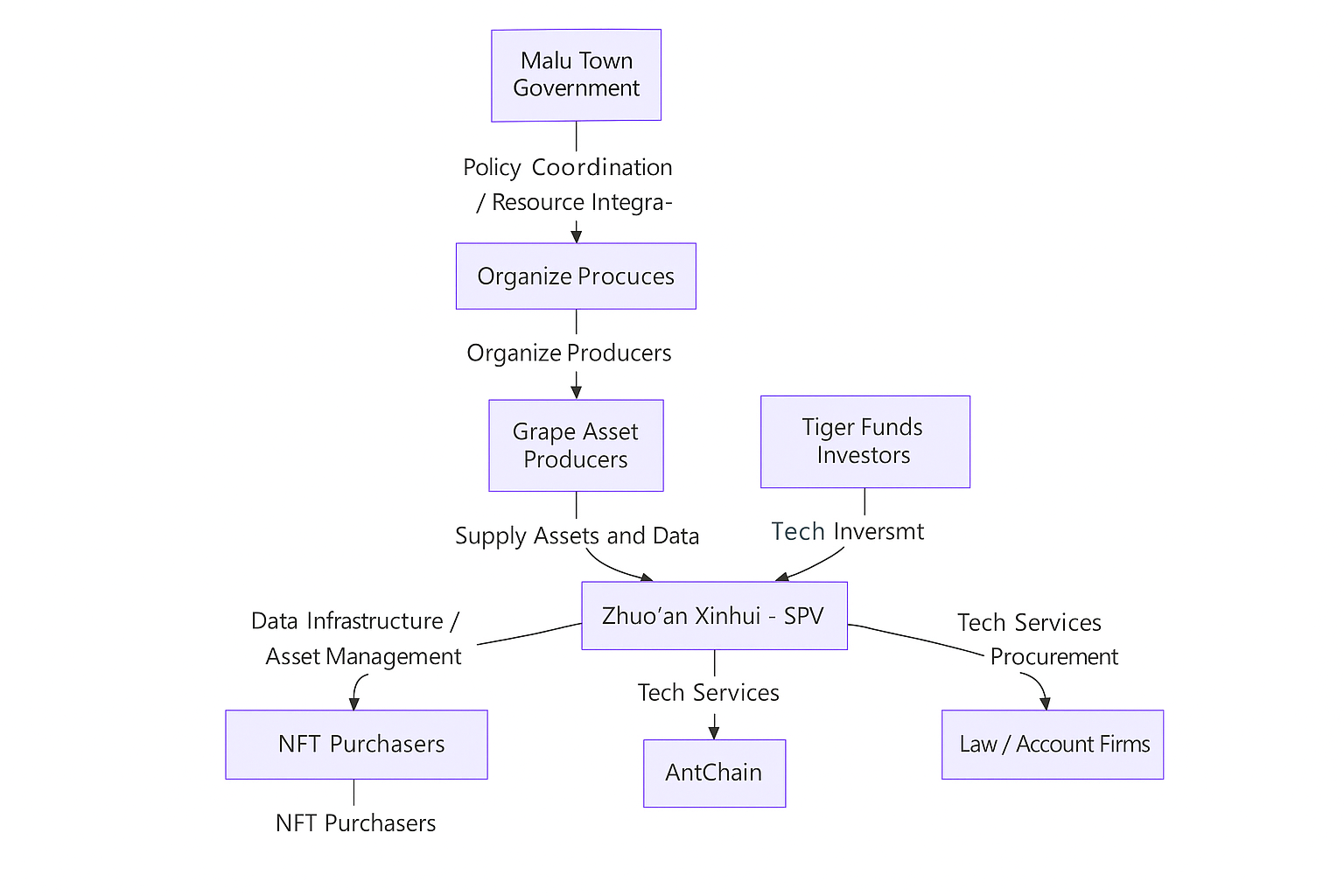

Tokenizing real-world assets (RWA) requires collaboration among multiple stakeholders. By mapping out all participants and their roles, we can reassess the Malu Grape project’s actual value from a holistic perspective.

Participants are categorized into two groups: core stakeholders and supporting institutions.

Core Participants

Zuo’an Xinhui (Project Operator): Responsible for integrating grape production data and brand qualifications, issuing NFT digital assets, and managing equity financing. It serves as the core executor of the entire project.

Shanghai Data Exchange (Compliance Platform): Provides on-chain verification services via the “Data Asset Shell” (DAS), builds the NFT trading infrastructure, and ensures regulatory-compliant disclosures.

Malu Town Economic Development Service Center (Government Coordinator): Provides policy support and resource coordination.

Malu Grape Producers (Underlying Asset Providers): Supply the physical grape assets and generate agricultural production data.

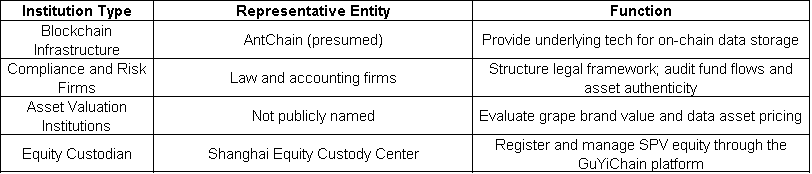

Supporting Institutions

Blockchain Infrastructure Provider (AntChain, presumed): Delivers blockchain technology for secure on-chain data storage.

Compliance and Risk Control (Law & Accounting Firms): Design legal frameworks and audit the authenticity of asset flows.

Asset Valuation Institutions (Unnamed): Provide pricing models for brand value and agricultural data.

Equity Custodian (Shanghai Equity Custody Center): Manages SPV equity registration via the “GuYiChain” platform, ensuring transaction transparency.

This structure shows that the Malu Grape project is essentially a government-guided, market-driven co-governance experiment. Through a triple-layered model—state-operated blockchain (Pujiang Chain), SPV legal structure, and a nested brand strategy—it balances compliance (avoiding security risks) and productivity (achieving 1.7x the average output per mu in Shanghai), representing a complex and coordinated economic initiative.

The Root Problem: Three Features That Reveal Its “Pseudo-RWA” Nature

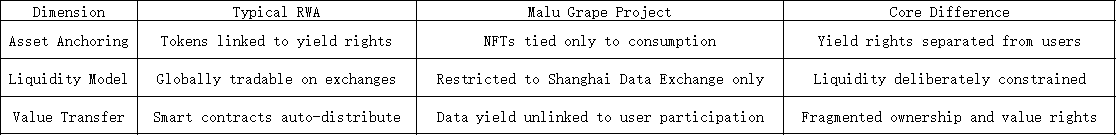

Dissecting the Malu Grape project reveals it is not a true RWA initiative, despite promotional claims. Here’s why:

A typical RWA token represents a share of real-world asset income and can circulate globally, with automated dividend distribution via smart contracts.

In contrast:

- Malu Grape issued 2,024 NFTs strictly defined as “digital collectibles,” tied only to product consumption rights (i.e., future grape redemption), with no claim to income.

- The NFTs are heavily restricted in circulation and function essentially as presale vouchers for agricultural goods.

- Holders receive grape delivery cards worth ¥200–300 and game points but gain no access to data-generated revenue. All income rights belong to institutional shareholders via the SPV.

- The project claimed to offer token-based income sharing, but in practice, NFT holders are completely excluded from the actual yield.

In terms of governance, decisions on varietal adoption or tech upgrades are fully controlled by the SPV, local government (Malu Town), and tech providers (AntChain). Public voting is absent, making the so-called “on-chain governance” a centralized mechanism, contrary to the DAO ethos.

In summary, the so-called Malu Grape RWA project is essentially a compliance-driven equity financing wrapped in NFT packaging. It is a “blockchain shell with a traditional finance core,” where technology serves to boost credibility rather than democratize ownership.

The entire project operates under strong government involvement, forming a distinctly Chinese RWA framework.

We should recognize the project’s true identity—as an equity financing model—but also its dual nature.

On one hand, it reflects a regulatory compromise; on the other, it showcases technical creativity under constraint. It offers a meaningful reference point for understanding the limits and potential of RWA innovation in China’s agricultural sector.

Read more: